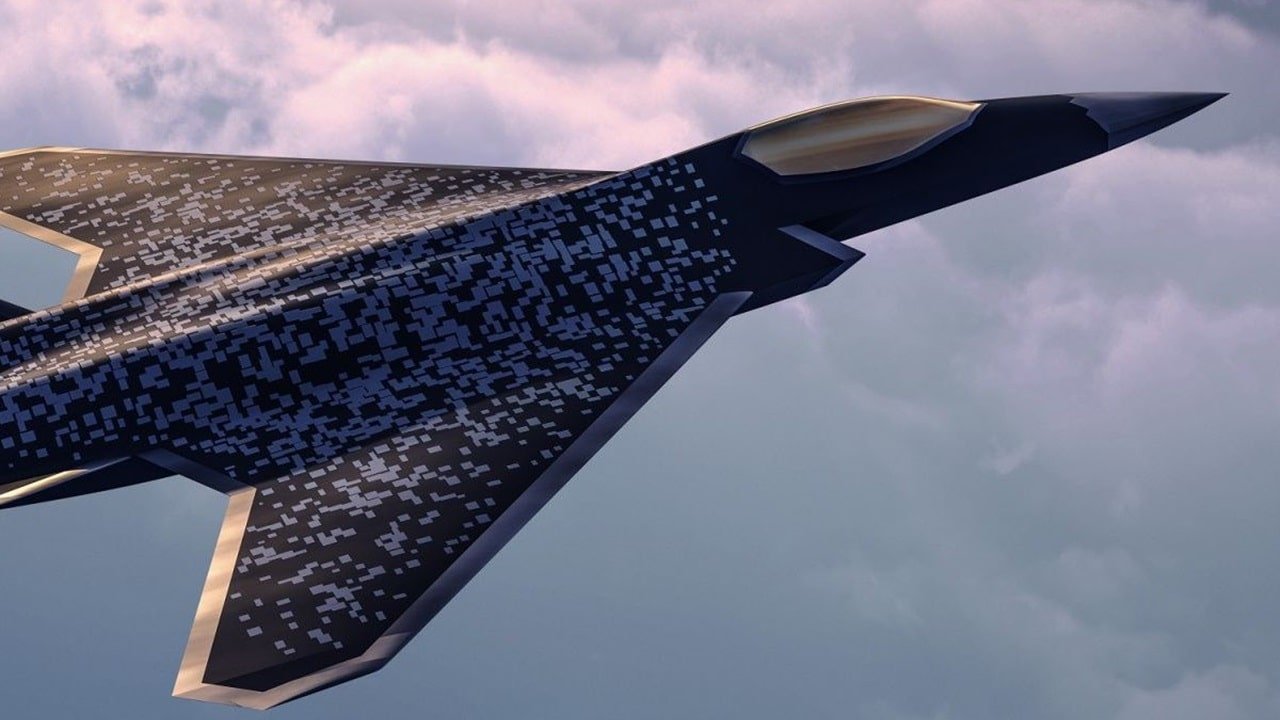

The Future Combat Air System (FCAS), once hailed as the centerpiece of European defense cooperation, is increasingly looking like a political and industrial casualty. The trilateral project between France, Germany, and Spain is on the brink, primarily due to deep-seated disagreements between the French prime contractor, Dassault, and the German-led industrial partner, Airbus.

The premise is stark: France, with its history of successful independent development like the Dassault Rafale, appears capable of going it alone on a next-generation fighter (NGF). Germany, which has not designed and built a crewed combat jet outside of a multinational consortium for decades (e.g., the Eurofighter Typhoon), faces a much tougher road.

This leaves Berlin at a crucial juncture. If the Next Generation Fighter (NGF)—the crewed aircraft at the heart of FCAS—is indeed dead, what are Germany’s options for securing its future air power and industrial base?

1. FCAS: The Fighter is Out, The Cloud is In

The most immediate path is a dramatic downsizing of the FCAS program to salvage what remains of the partnership.

- Focus on the “Combat Cloud”: Both France and Germany agree that the Combat Cloud—a multi-domain, data-rich network that connects all manned and unmanned systems—is critical. Germany, in particular, has shifted its focus to this aspect, which is less about the physical plane and more about the digital backbone of future air combat.

- The German Alternative: CFSN: Berlin is actively developing an alternative framework called the Combat Fighter System Nucleus (CFSN). This project aims to deliver Europe’s first operational Combat Cloud and a family of indigenous Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA)—unmanned drone systems that will fly alongside manned fighters.

- Interoperability Framework: If the NGF is scrapped, FCAS could simply become a “coordination framework for interoperability” between national systems. This allows Germany to proceed with its own digital-centric system while keeping the door open for data-link compatibility with France’s future plane (the potential Rafale successor).

By prioritizing the Combat Cloud and unmanned systems, Germany can secure industrial leadership in a key future technology, even without leading the construction of a crewed fighter.

2. The International Pivot: Backing a Rival or Seeking Component Roles

If a divorce from the NGF component of FCAS is inevitable, Germany has three key collaborative choices to produce a future fighter platform:

A. Enlisting in GCAP (Global Combat Air Programme)

This is the most likely and discussed alternative. The GCAP project, led by the United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan, aims to develop a rival 6th-generation fighter by 2035 (often referred to by its former name, Tempest).

- The Appeal: GCAP offers a multinational, equal-partner model with a clear development timeline. Italy has openly welcomed the possibility of Germany joining, noting that more partners increase the investment and reduce costs.

- The Challenge: Joining at this stage means German industry would likely be relegated to a lesser role. Industrial workshare arrangements are already being ironed out, and Berlin may not secure the high-value design and integration jobs it sought in FCAS.

B. Reaching Across the Atlantic

Germany’s purchase of the US-made F-35A as a replacement for its aging Tornado fleet—and for its nuclear-sharing role—already demonstrated a willingness to rely on US technology for critical capabilities.

- Component Manufacturing: Germany could use its industrial power to secure vital roles in a next-generation US program, such as the Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter. This means providing key subsystems like avionics, sensors, or mission systems. This is essentially enlisting the US to produce the platform, while Germany secures vital component work.

- The Trade-Off: This path guarantees access to cutting-edge technology and a proven supply chain, but it comes at the cost of European strategic autonomy and places Germany under American export control rules for a core air capability.

C. Forging a New Partnership (Sweden/Spain)

Germany could attempt to lead a new, smaller consortium built around its specific operational requirements, possibly with partners who share a common industrial heritage or similar needs.

- The Nordic Connection: Sweden, with its advanced industrial base and experience with the Saab Gripen fighter, has been named as a potential fallback partner. A German-Spanish-Swedish fighter concept could focus on long-range interceptor and air superiority roles, which align well with German and Swedish defensive strategies.

3. Germany’s True Industrial Play: Beyond the Manned Fighter

The core of the issue is not just flying a plane, but maintaining a domestic industrial and technological base. Germany’s largest industrial contribution to past projects has often been in sensors, electronic warfare, and data management—the brains of the system.

Instead of backing down, Germany is strategically shifting the definition of “future fighter” to play to its strengths.

| Option | Primary Focus | Benefits for Germany | Drawbacks |

| Downsized FCAS (CFSN) | Combat Cloud / Unmanned Systems (CCA) | Domestic leadership in digital/AI backbone; Industrial lead on drones. | No German-led crewed fighter; Reliance on partners for manned aircraft. |

| Join GCAP (UK/Italy/Japan) | Crewed 6th-Gen Fighter | Access to a cohesive, successful program; European-led platform. | Reduced industrial workshare/influence due to late entry. |

| Component Role (US/France/UK) | Subsystem Production | Secure high-value component work (e.g., sensors, avionics). | Loss of strategic autonomy; Dependency on foreign export rules. |

Conclusion: The Race for the Cloud

The notion that Germany must “back down” is a simplification. While it may lack the indigenous capability to design and build a crewless fighter from scratch as fast as Dassault, its industrial strength in the “System of Systems” is formidable.

The current trajectory suggests Germany will move to salvage the digital heart of FCAS by focusing on the Combat Cloud and its own CCA program (CFSN). This allows it to protect its industrial base while securing a next-generation battle management capability. For the crewed platform, a quiet pivot to the GCAP consortium, or securing major subsystem roles with a key ally, seems highly probable.

The FCAS Next Generation Fighter may be dead, but Germany’s pursuit of a future combat air system is very much alive, shifting from the airframe to the artificial intelligence and data links that will define air power in 2040 and beyond.