In the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, a new wave of radical social thought swept through the young Soviet state. Old laws were shattered, and questions of marriage, family, and sexual freedom became feverishly debated, particularly among the youth.

But the revolution’s chief architect, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, had a surprisingly sharp and suspicious take on the era’s fashionable “sex theories.” His famous, candid reflections on the matter—recorded by his comrade Clara Zetkin—reveal a mind focused relentlessly on the political struggle, viewing excessive interest in sexual matters as a dangerous distraction, a form of intellectual decay, and ultimately, a disguised tribute to the very system they sought to overthrow: bourgeois morality.

The ‘Glass-of-Water’ Theory: A Proletarian Peril?

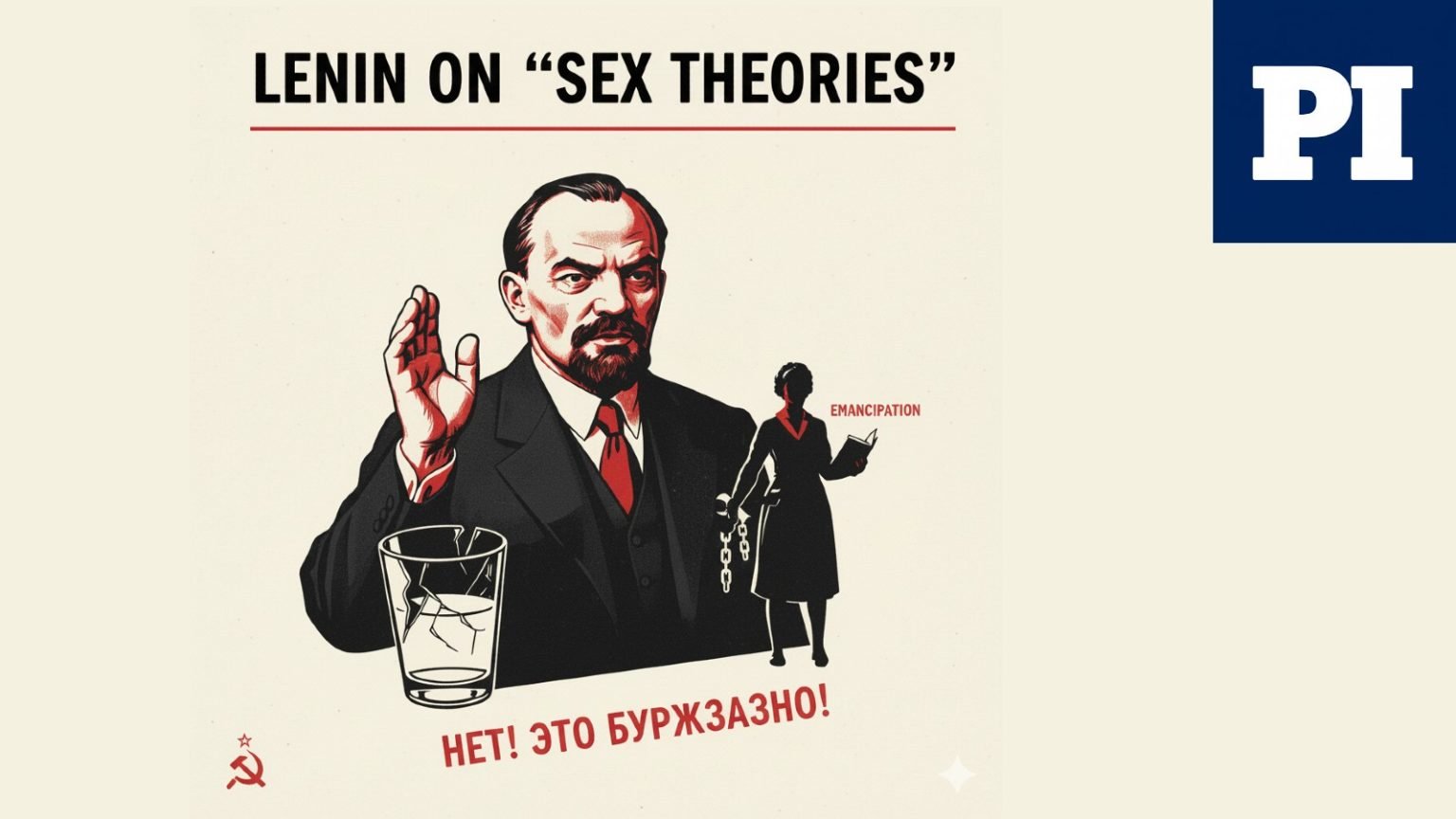

One of the most radical notions circulating among some revolutionaries was the so-called “glass-of-water” theory, which suggested that satisfying sexual desire should be as simple, easy, and inconsequential as drinking a glass of water in a communist society.

Lenin dismissed this theory outright, calling it “un-Marxist” and “anti-social.”

“The drinking of water is really an individual matter. But it takes two people to make love, and a third person, a new life, is likely to come into being. This deed has a social complexion and constitutes a duty to the community.”

For Lenin, sex was not just a simple physical act, but a social phenomenon with profound consequences. He argued that the revolution demanded concentration, discipline, and the conservation of energy. He saw casual promiscuity and “sexual exaggeration” as a form of “dissoluteness” that was inherently bourgeois—a sign of decay, akin to alcoholism, that weakened the necessary resolve of the revolutionary class.

Mistrusting the ‘Superabundance of Sex Theories’

Lenin’s most potent critique was leveled not just at behavior, but at the intellectual obsession with sexual liberation that dominated some circles, often influenced by thinkers like Sigmund Freud (whom Lenin called “fashionable stupidity”).

He viewed the abundance of articles and treatises on sex theory that flourished after the revolution as a red flag:

“I mistrust those who are always absorbed in the sex problems, the way an Indian saint is absorbed in the contemplation of his navel… It seems to me that this superabundance of sex theories… springs from the desire to justify one’s own abnormal or excessive sex life before bourgeois morality and to plead for tolerance towards oneself.”

In this stunning observation, Lenin flipped the script: the so-called “sexual liberation” was, paradoxically, a veiled attempt to seek approval from the very conservative morality they claimed to be rejecting. By constantly analyzing and debating sexual norms, they were granting the topic an undue level of importance, elevating it to the center stage of revolutionary thought.

He concluded that this intellectual preoccupation was “thoroughly bourgeois,” a “hobby of the intellectuals,” and had no place in the class-conscious, fighting proletariat whose focus must remain on the transformation of the economic structure.

The Core of Communist Morality

While Lenin rejected the obsessive focus on individual sexual liberation, he was an unwavering advocate for the complete legal and practical equality of women. The Bolshevik decrees of 1917 and 1918 were revolutionary in practice: they legalized abortion, made marriage a civil contract, simplified divorce, and actively worked to transfer domestic and child-rearing duties to the state (with the creation of creches and public kitchens).

For Lenin, the real emancipation of women—and the true destruction of bourgeois marriage—lay in freeing them from domestic slavery and dependence on men, integrating them fully into social production, and ensuring their political and economic rights.

Ultimately, Lenin’s morality was subordinated to the interests of the proletarian class struggle. The goal wasn’t simply to trade one set of sexual rules for absolute license, but to create a new, healthy, disciplined social order where sexual relations—like all other aspects of life—fostered the strength and unity of the communist project.